Best Email Signing and Encryption Solutions

Hi and welcome! I was honored to present this topic at #dc4420. You can read here everything I presented if you’d like to run through some things one more time. I addressed yesterday’s questions at the end of the article. You can always drop me an email if you have questions and if I can help, I will.

I would like to introduce you the most known standards and the best solutions in my opinion that make email security easier.

1. PGP & S/MIME

There are two well known standards for email cryptography: OpenPGP and S/MIME. PGP is one of the most known implementations of OpenPGP and it is commonly referred to talk about it.

If you don’t know how symmetric and asymmetric (known as public-key encryption as well) work, I recommend you to look into them, not specifically for this topic – you’ll hear about them a lot. If you don’t know where to start, I recommend you these videos

1.1. PGP

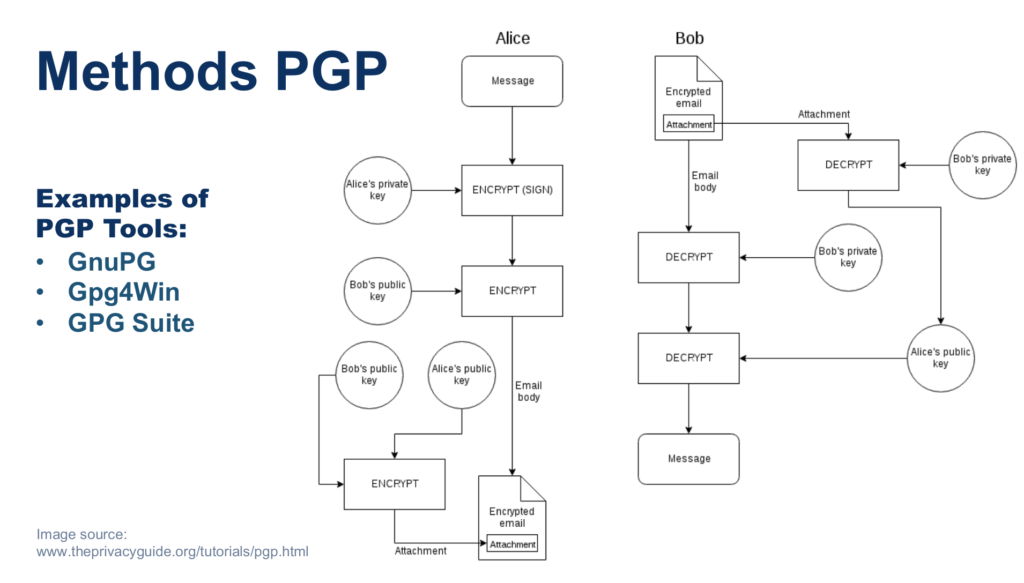

There are multiple designs for the implementation, but all of them are based on the same concepts: each user has a pair of private and public keys and through a so called “web of trust” they are able to exchange their public keys. You can think of “web of trust” as a safe environment or mechanism to exchange the public keys with whoever you want from your group, without worrying that someone tampered the keys. They will keep their private key for themselves and use it either to sign messages and prove they are who they say they are (as they are the only one having the private key) and they will use the other person’s public key to encrypt messages for that person (the other person will decrypt them using their private key).

This implementation in particular follows the following workflow: Alice signs the message she sends to Bob (in an inefficient way) by encrypting it direclty with her private key. Then she encrypts it one more time with Bob’s public key. Bob will need to do the same steps in reverse order, so he is the only one who will be able to decrypt this final blob, and then by using Alice’s public key he will at the same time get the message in plain text and ensure Alice’s sent the message as her public key worked for decryption.

The problem with PGP is that it is complex to use, it assumes the existence of a web of trust (this is mentioned a lot although there are solutions such as the one provided by MIT) and even more, it is not backwards compatible. So, to use it to talk with others, everyone needs to have the same version of PGP.

1.2. S/MIME

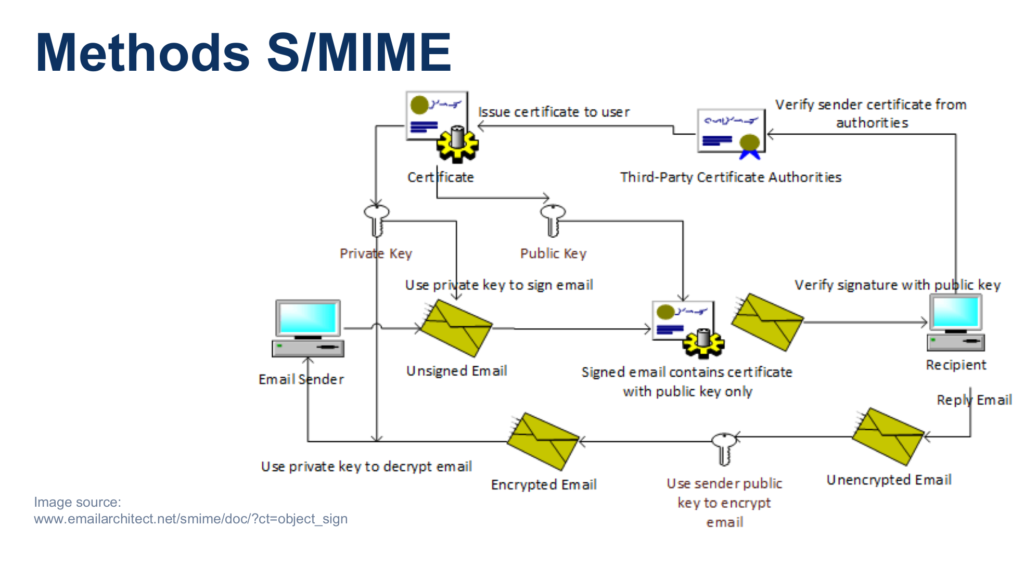

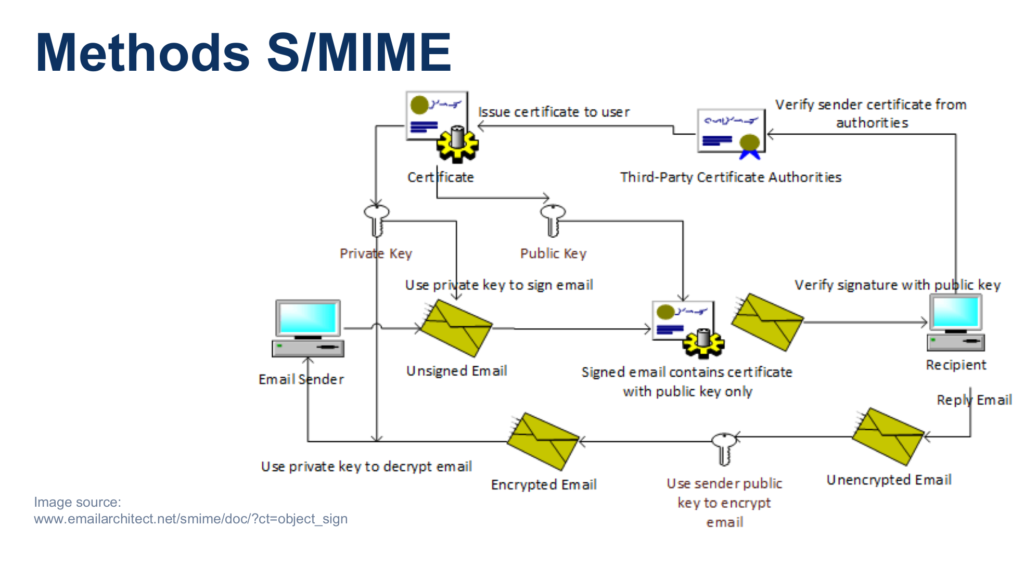

S/MIME works based on certificates. There is the concept of CA (Certificate Authority) which are mainly entities allowed to create and revoke certificates for others and they are generally trusted. To use S/MIME, you have to request such a certificate from a CA, which might cost you starting with 40$ per user per year. If you use S/MIME only internally, inside your company, and your domain certificate allows you to create S/MIME certificates, then you can create your certificates for free. They won’t be valid outside the company though. That completely skipped out of my mind yesterday 🙂

The certificate has 2 parts, a private and a public key. The rest of the workflow works as typical asymmetric encryption and digital signatures do. If you want to sign a message (second horizontal line in the image above), you would hash the message, encrypt the hash with your private key and send this to the recipient along with the unencrypted message and the public key. When he receives the message, he will firstly verify that your public key is valid by contacting the CA, then it will do the normal digital signature validation process. For encryption (third line right to left), you will encrypt the email with the other person’s public key.

2. Email Authentication: SPF, DKIM, DMARC

There are five known email authentication standards, of which the first three are the most important: SPF, DKIM, DMARC.

- SPF: by using SPF, you can assign a list of allowed IPs for the mail servers to the DNS records. When an email is sent through a mail server from a different IP address than the ones registered for that domain, the SPF validation will fail. It does not mean the sending will fail, the SPF validation has to be checked.

- DKIM: it allows you to associate a public-private key pair to your mail servers. You would keep the private key on your mail server and relate the public key one to your DNS record. In this way, emails will get a signature attached to them and when a mail server receives them, it will look up for the public key and validate the digital signature. In this way, you can ensure the mails you sent are not tampered with and you can prove they came from you.

- DMARC: both the SPF and DKIM have one issue: they check the domain validity, but they don’t check that the same domain is used in the from header (they look for different headers, not the From header). For example, you could create your own domain A, whitelist your mail server IP for the domain A and send an email from there. Your IP would be allowed for A, so your mail will pass the SPF validation, no matter if in the from field you put domain B such as From:someone@B. In the same way, you could assign a key pair to the same mail server on domain A and when you send your email from there it will be signed as being from A (which it is) and validated as being from A, even in the from field you put again someone@B. DMARC has the purpose of making sure that what SPF and DKIM validate is indeed what is written in the From field. Also, DMARC can tell the receiving mail server what to do with a mail that failed the verification and it can report to the owner of the spoofed domain details about the incident.

- ARC: this is not as important, but shortly it addresses one issues DMARC has: when forwarding an email, the From field value changes and the DMARC validation fails. For that, ARC follows the entire thread of that email and it looks if the mail was modified at any point.

- BIMI: I wouldn’t call this security, if anything I would call it misleading (but this is just my personal view). By using it, you can brand you email, “showing” that it is from you: you can add you graphic banners, your logo etc.

3. ProtonMail vs Tutanota

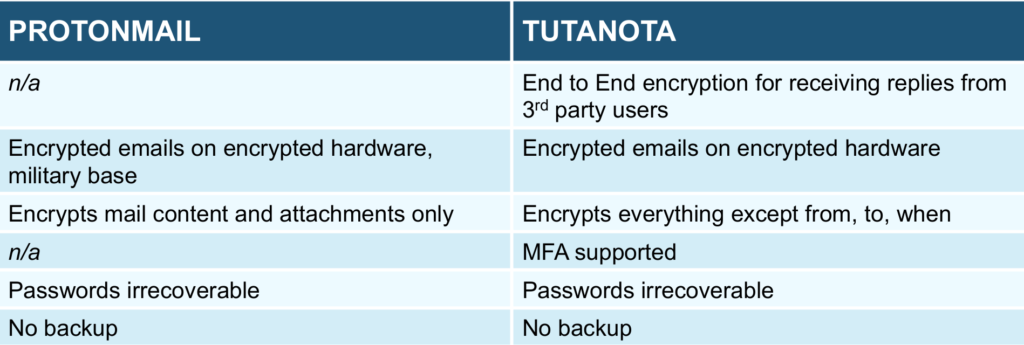

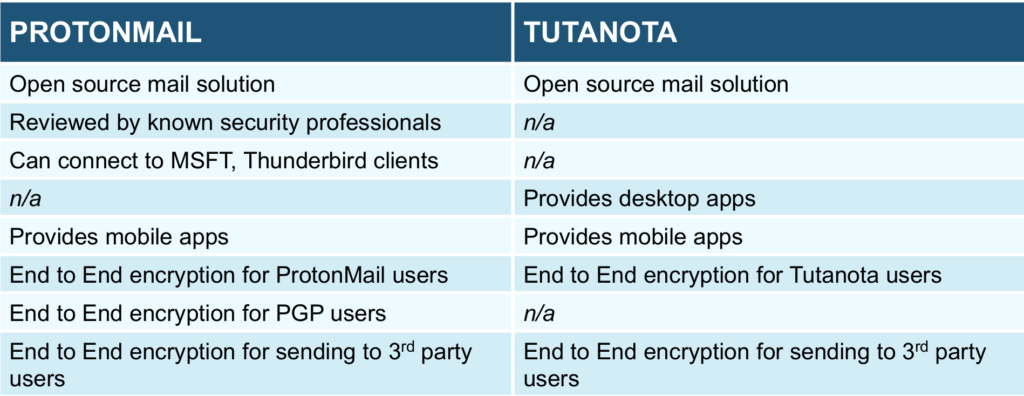

ProtonMail and Tutanota are both email providers that decided to include email encryption and digital signing as one of their main features. There are others, but these are the most used and the most advanced ones. Here is a comparison between these two (details following the pictures):

- code: both of them are open-source, ProtonMail having the advantage that the code was reviewed by known cryptographers.

- mail clients: both of them provide web clients and mobile clients. Tutanota provides also its own desktop clients for Linux, Windows, macOS. On the other side, ProtonMail provides bridges with other mail clients such as Outlook and Thunderbird, meaning you can integrate it with them and work as you did until now, but take advantage of the email encryption and digital signing provided by ProtonMail.

- encryption: both of them provide end to end encryption (from you device to the other person’s device) if both ends of the communication use their service. If only one uses it, then ProtonMail can provide end to end encryption between a ProtonMail account and a custom PGP one (though you will need to do some manual configuration), while if the other person uses a known email provider (such as Google, Yahoo, MSFT), then they can encrypt from your side to their, but not in the opposite direction. Unlike ProtonMail, Tutanota can also receive encrypted replies to encrypted emails sent from a Tutanota account to a non-Tutanota one. The way both of them do encryption between their service and a 3rd party one like the ones mentioned above is by sending an email containing a weblink where the recipients have to go and put a password (agreed by both parties, by using another communication channel) to get access to the unencrypted contents of that email. That password is known only by the two parties and it is actually used as a symmetric key to encrypt the email.

- hardware: both of them keep the email encrypted on encrypted hardware, ProtonMail having their datacenter based in a former military base in Switzerland (if anyone thinks that matters…).

- encrypted contents: Tutanota encrypts more things than ProtonMail: it encrypts everything except the from, to and when headers needed for routing the email. ProtonMail can encrypt only the contents of the email and the attachments.

- passwords irrecoverable: both of them ask you to choose two passwords: one of them is the account password, the other acts as the private key in the public-private keys pair used to sign and encrypt/ decrypt your emails. The account password is used to encrypt the private key and they both live on your local system, so if you loose any of them, the provider is not able to recover them, nor your encrypted emails.

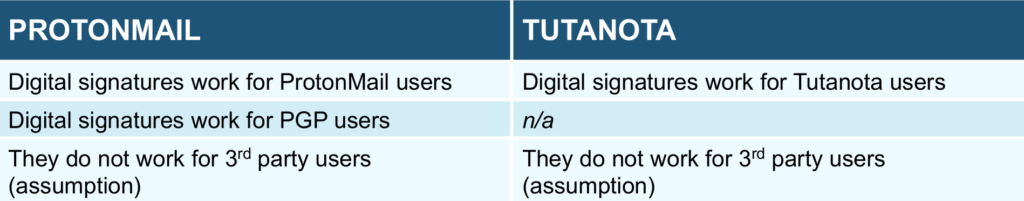

- digital signatures: they work well when both the users have ProtonMail or both Tutanota, but I assume they do not necessarily work well when one end uses another email provider, as that one does not necessarily have a mechanism (following the same protocol) to check the signature is valid.

4. Microsoft Solutions

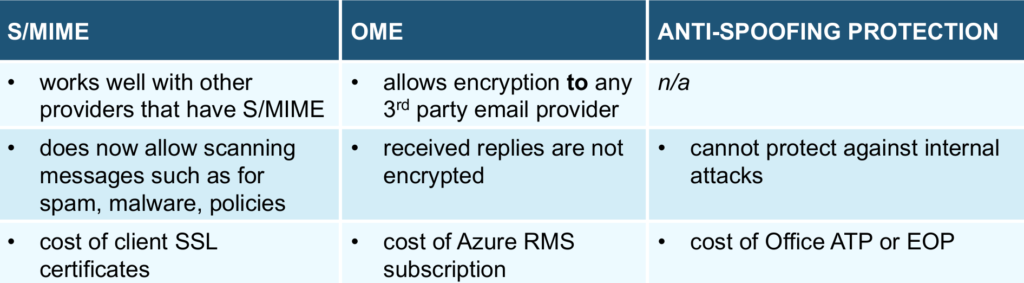

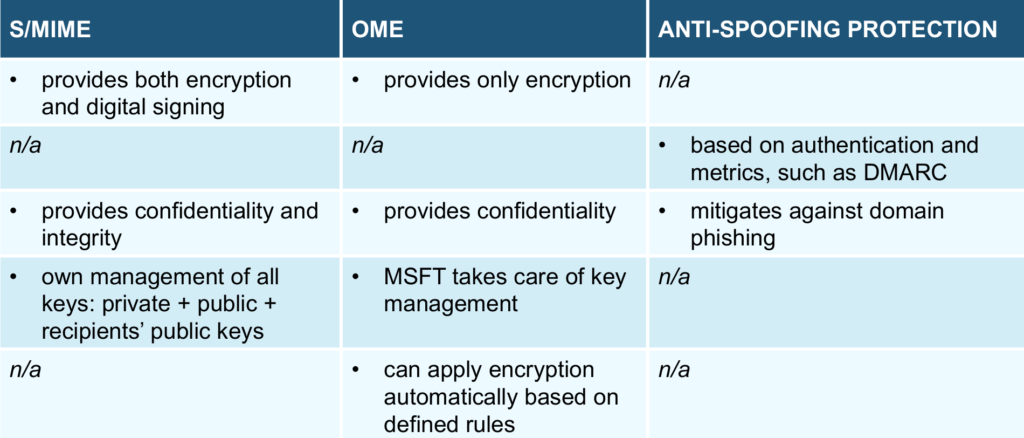

There are about five Microsoft solutions to ensure confidentiality, integrity and to mitigate phishing attacks for their own mail products, of which three are the most important: S/MIME, OME (Office Mail Encryption), Anti-Spoofing Protection. Following, there is a comparison between these three solutions:

- goal: the goal of each product is quite distinct: S/MIME is able to do both encryption and digital signing so it can ensure both confidentiality and integrity, OME can do only encryption, the Anti-Spoofing solution can only mitigate against domain spoofing attacks.

- key management: the first two are based on public key cryptography, so keys need to be managed: for OME, Microsoft happily takes care of all your keys (the private one is stored locally). For S/MIME you have to store you private key locally, distribute your public key to others and then record their public keys.

- email authentication: the Anti-Spoofing solution is based on email authentication (SPF, DKIM, DMARC) and has other metrics as well, such as they can take actions if someone sends an email from an IP but that person is not logged into their products from that IP.

- automatic encryption: OME has the advantage that it can apply encryption automatically if some policies are matched (such as if the mail contains some sensitive words).

- compatibility: their S/MIME solutions works well with other solutions based on S/MIME. The OME solution is able to send an encrypted email to a client based on another email provider, but it cannot receive back encrypted emails. The way it does it is through a MSFT portal where the receiver can either login either enter a OTP and get access to that email. As you can see, this is not end to end encryption, but at most from your device to MSFT’s portal.

- S/MIME downsides: S/MIME encryption works end to end and it will scramble the contents of the email, meaning that any tool you have in between those two ends, such as tools that look for broken policies, phishing or malware, won’t be able to match the text so they won’t work (unless you replace them with another MSFT solution and give up encryption at their point). Also, S/MIME certificates are not free as the domain ones can be. Their cost can start around 40$ per user per year.

- OME downsides: as specified above, when one of the end does not use MSFT email products, they won’t be able to receive encrypted replies. For this one, a subscription is needed to Azure RMS, which cost around 1.5$ per user per month.

- Anti-Spoofing Protection downsides: a subscription is needed for this one as well, about the same amount as the above one. Also, as it looks mostly for domain authentication and IPs rather than usernames, it does not work to prevent domain phishing attacks when the attacker is an insider.

5. Final thoughts and yesterday’s questions

- S/MIME certificates costs: if you want to use them internally, such as to know if an employee sent an email or he was impersonated, depending on your domain certificate, you might be able to create these certificates for email usage for free. For external usage, the price is the one mentioned above.

- Domain Typo Squatting: if you’re worried someone will slightly modify the domain name and you would miss it, then this is my answer: if you’re talking about your internal domain, then you could enable S/MIME for it and train your employees to look for the “lock” icon proving that comes from who it should. If the icon is missing, it doesn’t matter if that’s a typo squatting or impersonation or anything else, they shouldn’t trust that email.

- Key length recommendations: these solutions use both symmetric and asymmetric encryption. I you use let’s say AES and RSA, 128 key length is ok for AES (the algorithm versions for the longer ones are vulnerable), 2048 for RSA is good (lower is vulnerable).

- Low adoptance: yes, email encryption and digital signatures are not that common. IT Corporates have it implemented, at least internally. That does not mean you cannot take advantage of them at least for some use cases, such as for internal usage to make sure someone does not trick an employee to do some action like moving money by impersonating another employee. Or if your board uses email to talk about strategies and critical data, ideas, products, you could provide them with a way to encrypt it. Finally, SPF and DKIM already gained a lot of popularity, DMARC is the next one people are trying to address against its setup difficulties. For these ones you don’t depend on the other end of the email conversation doing something on their behalf.

I hope you found this useful and you’d at least keep these standards and solutions in mind for that time when you can address the email security issue. ‘Till next time!