How Does The Zero-Trust Architecture Work

Hi everyone! It’s been a long time since I’ve written anything, so hopefully this blog post makes up for it. Zero-Trust is such a buzzword these days and yet there is little documentation online on how to build one. I recently read the “Zero Trust Networks” book by Gilman & Barth (which I recommend 100%), so I decided to share my notes and my thoughts in this article, should anyone not have the time to go through the entire book. Hope you enjoy it and find it useful!

WHY AND WHEN TO USE THE ZERO-TRUST ARCHITECTURE

Sometimes your threat actors list may not justify the cost of using a Perimeter-based model. Zero-Trust is not inexpensive either, but it may be more feasible. Sometimes you already use a Perimiter-based model but you feel that it fails you and you feel trapped between taking all the risks to keep the network as it is, and having to redesign your network, or parts of it. Depending on the complexity of your network, redesigning it might come with an incredible amount of effort and costs.

Other times you may simply wonder how much you should really trust your network. Did you have significant incidents in the past and you really can’t tell whether you successfully eradicated them? Is your network improperly designed, like not well segmented, segregated or left somewhat open? Are you concerned of how disgruntled employees might act? Are you using public cloud and the fact of sharing the same infrastructure with other tenants makes your worried?

These are just a few examples, but the list can go on and on. Did you notice a pattern in all the above scenarios? All assume that a threat actor already breached your perimeter, and they are in. The network is assumed to be hostile, compromised or simply not to be trusted. It is concerns like this that the Zero-Trust model tries to help with and that might drive you to consider using it.

THE ZERO-TRUST MODEL

You can think of the Zero-Trust model as another layer applied on top of your network, that abstracts your network design and whether it’s secure or not. This new layer tries to secure and verify all the network communications, no matter their source or destination. Given that it abstracts your network design, you could use both the Perimeter model and the Zero-Trust one, in line with the “secure in depth” principle. It’s up to you to define if it’s worth it, cost-wise. Generally speaking, of all the issues mentioned above, your biggest drive to use Zero-Trust might be an improperly designed network or a significant past incident.

You have to know that the Zero-Trust model is not meant to protect you from APTs or even privileged employees. As such, it’s not meant for industries like finance, which experience an advanced level of attacks. However, most companies do not really get to experience this level of attacks. If you assessed who your attackers are and they are not APTs and you don’t worry extremely about your privileged employees, then Zero-Trust can be the right solution.

Zero-Trust is largely based on configuration management, as it is only feasible and scalable when fully automated.

In a Zero-Trust model you mainly care about 3 things:

- the user/ application authentication. Applications are seen as similar to users at a design level

- device authentication. The devices, just like the users and applications have to be authenticated and authorized.

- the notion of trust. See Trust Score further down.

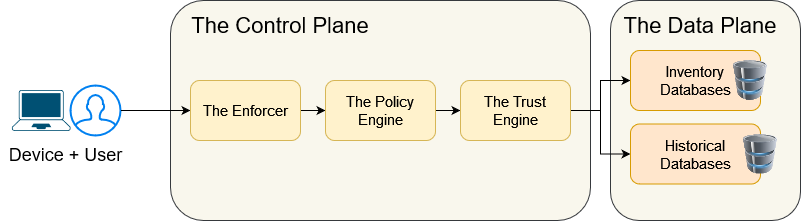

And finally, there are 2 main components when building a Zero-Trust model, which are further detailed:

- The Control Plane

- The Data Plane

THE CONTROL PLANE

The Control Plane handles the requests. It authenticates the user or application and the device and then manages their requests for access to protected resources. The Control Plane is ultimately an authorization system, which will either allow or deny the request. To authorize a request, the system fetches a policy and checks if the request is qualified to access the resources it wants, based on the policy. Being qualified means that the user/ app and the device that sent the request have an aggregated Trust Score over some threshold defined in the policy and comply with other criteria ie. having the right user role to access that resource. If the request is allowed, then the tuple (user/ app, device) gets a short-lived certificate or a leased access token. If sniffing is a concern, then encryption should be used, often in the shape of certificates. Authentication in Zero-Trust is often based on certificates, too. Having authorization, authentication and encryption ensures that each network flow is authentication and expected. The security of the Control Plane itself is, of course, essential.

The Control Plane has 3 isolated components, which will be further detailed:

- The Enforcer

- The Policy Engine

- The Trust Engine.

THE ENFORCER

The Enforcer is typically a very lightweight component, which does the following:

- it receives requests

- it asks the Policy Engine if they should be allowed

- and then enforces the response it received.

The Enforcer should exist in large numbers and should be placed as close as possible to the workload, to ensure low latency. It can either be a proxy, a load balancer, a firewall or it can be a client application installed directly on the endpoints and servers.

In a mature Zero-Trust design, the Enforcer would apply also on the Zero-Trust components (such as on the Control Plane itself).

THE POLICY ENGINE

The Policy Engine decides if a request should be allowed. Here is how it works:

- it receives a request from the Enforcer

- then asks the Trust Engine to compute the Trust Score for the request and get some other useful data

- it pulls the Policy for the resource it tries to access

- then it decides if the request should be allowed, based on the Policy and the response it received from the Trust Engine

- sends back the response to the Enforcer

A policy is simply a set of conditional statements under which a request is allowed/ denied accessing a resource. It’s worth mentioning that the policies can be layered (broader policies, then more and more granular ones) and they should be fine-grained. Given that this can place a burden, the effort should be distributed across teams - each system owner maintains the policies for that system. Before enforcing the policies, their impact on the network flows should be monitored for some time, for fine-tuning.

Finally, the Policy Engine is modeled as a service, with its own CI/CD pipeline: it stores the policies in a version controlled system and every time a policy is updated, it is promoted up through the CI/CD pipeline.

THE TRUST ENGINE

The Trust Engine is a service used by the Policy Engine mainly for risk analysis and it delivers 2 things:

- a Trust Score in a numerical format

- other metadata about the user/ application and the device making the request

These 2 deliverables are often bundled as one in a lightweight JSON response. (The book calls this JSON “the agent”, but personally I do not agree with this terminology - I would call the Enforcer an agent, given that it’s a lightweight client app).

The Trust Engine works like this:

- receives a request from the Policy Engine

- pulls data about the user/ app and the device from the Data Stores

- computes the Trust Score

- creates the JSON

- sends the JSON back to the Policy Engine

It’s worth mentioning that the score should not be exposed to end-users, so they cannot maneuver it. Also, the Trust Engine should include conditional logic to handle unknown attack vectors too.

THE TRUST SCORE

The Trust Score is purely a numerical value that associates a level of trust with a (user/ app, device) tuple. If having a trust score for the user/ app and the device seems contradictory for you when discussing a Zero-Trust Networks system, recall that it’s really the networks that you don’t trust. You still have to trust something for authorization purposes.

There are 2 main problems a trust score system has to solve:

- sourcing a trust score when there is no trust

- managing trust.

Sourcing Trust

When there is no trust, you need to have a mechanism to source it from somewhere. A common method is Trust Delegation. Trust Delegation is kind of transitory relationship: you trust component A, component A spins up component B, so you trust component B. An easy example is trusting a new system because you trust the provisioning system. And about that, a new system is more trusted than one that hasn’t been imaged/ rotated for years, as it has a smaller chance of being already compromised.

Trust may need to be sourced also if the score gets too low to allow access to some resource that the (user/ app, device) tuple should really have access to. Some methods for this are: having management approval, visiting the IT department, having an additional MFA push etc.

Sourcing trust allows us to build scalable and automated systems and to operate without too much human intervention.

Managing Trust

Unlike the way firewalls work, Zero-Trust Networks think of trust as a moving target. Trust is dynamic and it can increase/ decrease based on both previous and current actions, much like in real life, so you need to have a way to re-evaluate the trust. You either re-evaluate the trust for each request, or based on a schedule. If scheduled, you might run in the situation where you handle a request differently than you would if you’d wait for the next scheduled run.

Trust is defined per user/ app and per device and then it’s aggregated in one single score, called the Trust Score. You can use any data that source that would define your trust: LDAP to get the user role, certificates to get the device type or other data you stored in them, UBA to get the user activity patterns, request frequency etc.

THE DATA PLANE

The Data Plane is used mainly to store all the data about the user/ app and the device in a persistent storage, so it can be queried in the future. The Data Plane has just one component type: the Data Stores.

A few things worth mentioning:

- it’s very likely that you’ll have significantly less data for autonomous systems than you have for humans

- certificates can provide useful data too: a device certificate could include data like the device type, the OS etc.; a user certificate could give you the user role

- there may be some PII you have to manage, by storing user data.

THE DATA STORES

Think of the Data Stores as the source of truth for the current and past state of the system: it holds the inventory databases and the historical databases. The inventory databases are just asset inventory databases and can be built using the configuration management. The historical databases hold anything worth storing about the user/ app or the device, that would influence the trust score, such as patterns, timing, frequency, accessed resources etc. There could be a database of expected flows, too.

The Data Stores are modeled as a service and interact with the Trust Engine. The effort to build it might have to be distributed across the organization.

LIMITATIONS

The Zero-Trust design does come with a few limitations, which you should be aware of:

- DDOS attacks are not prevented and you should use a specialized system for that

- Although it’s using encryption, privacy is not guaranteed: ie. you can still see which package is routed from where to where, even if you cannot see the package content

- Social engineering should still be addressed outside this system

- And most importantly, the invalidation of trust can occur before the policy is polled again. Should you need to revoke the trust for an agent, you can only do it next time the enforcement component checks the policy, not in between, given that it’s a polling system. Pushing invalidation adds significant complexity, hence polling is generally preferred for Zero-Trust.

GETTING STARTED WITH ZERO-TRUST

If you’re just getting started with the Zero-Trust model, there are a few things to keep in mind. Firstly, only move to Zero-Trust if it makes sense (see the very first section). Secondly, start small. You don’t need to move all your internal networks and network flows at once. Choose a small scope, increment over it, get your system ready and only then scale it to the rest of the networks. Thirdly, if you don’t have an asset inventory, use your configuration management to build one and if you don’t authenticate devices, start doing it. Fourthly, whenever covering a new network, don’t enforce the policies immediately. You should allow for a long period of time just to log the network flows, monitor how the policies would behave and fine-tune them. Otherwise, you’ll end up with frequent situations when someone has to intervene, which will make the system fail altogether.

That’s pretty much it! Not as complex as it sounds, is it? If you’d like to go into more details, I really recommend the “Zero Trust Networks” book. I hope you enjoyed the article and I’ll see you on the next one!